The town of Hinah is located on the eastern slopes of Mount Hermon, 47 km southwest of Damascus, at an altitude of 1,100 meters above sea level. It is built on a natural volcanic hill covered with archaeological remains dating back to ancient periods, most notably the Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic eras. Throughout the town and its surroundings, numerous structures, presses, caves, architectural elements, tombs—either built or carved into the rock—and stone quarries can be found. Many stone inscriptions are present as well, written in Greek, Latin, Safaitic, and early Arabic scripts.

The Damascus Countryside Antiquities Directorate conducted several archaeological surveys and excavation seasons in the town and its surroundings from 2003 to 2011. These studies revealed that the earliest settlement in Hinah dates back to the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, while the most significant periods were during the Roman and Byzantine eras. Settlement in the town continued without interruption throughout the Islamic periods up to the modern era.

Firstly: Hinah in the Middle Bronze Age:

Discoveries from this period were found at Tell al-Kurum, located less than 300 meters east of Tell Hinah. In its upper section, two collapsed collective burials were uncovered, dating specifically to the period between 1800 and 1750 BCE.

The tombs are of the “shaft” type, which had been common in the region since the 3rd millennium BCE. They were found beneath a layer containing Roman-era graves and coffins; the excavation of that upper layer caused damage to these Bronze Age tombs, collapsing their ceilings along with the funerary furniture and skeletal remains inside.

The evidence suggests that these tombs were used for burial over a relatively long period, possibly each serving a particular family or clan.

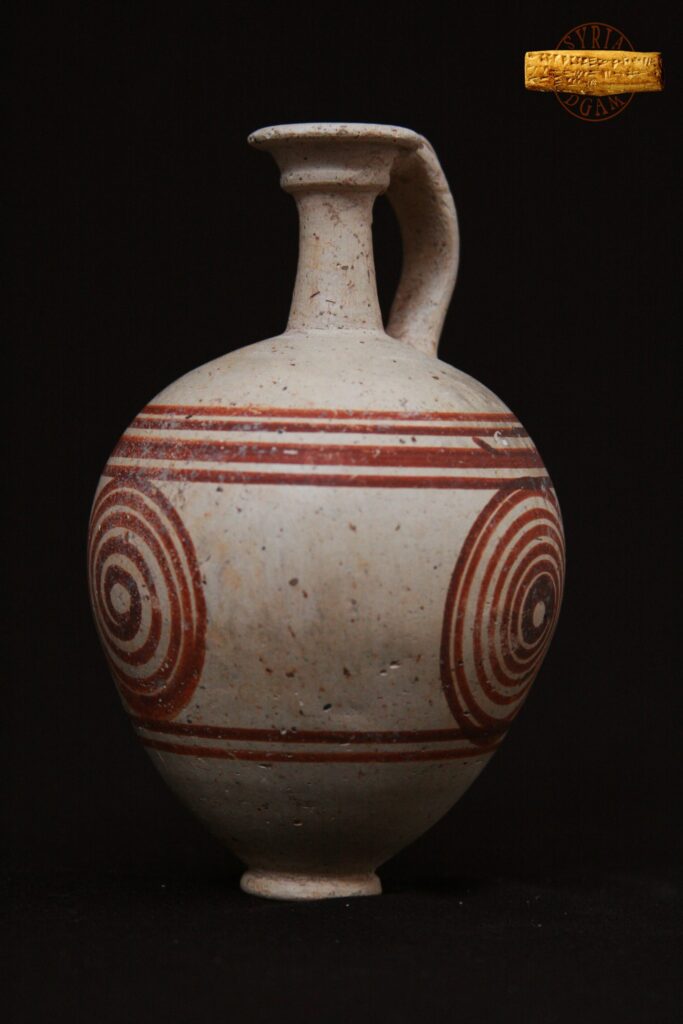

Scattered human skeletal remains of children and adults of both sexes were found in various positions. Several metal objects, such as axes and clasps, were also discovered, along with dozens of highly distinctive pottery pieces. Among them were small ritual vessels with ring-shaped forms, jars with three-legged bases resembling loops, plates, bowls, cups, bottles, and Syrian oil jugs—many decorated with striking black and reddish-brown lines. Some jugs resembled pottery from Tell el-Yahudiya and Tell el-Farah in Egypt, as well as pottery from the Syrian coast and other sites in Syria, Palestine, and Jordan.

Secondly: Hinah in the Roman Period:

Numerous architectural remains and structures from this period are scattered throughout the town and its surroundings, including column bases and capitals, parts of columns, altars, pedestals, coffins, jars, carved stones, and more. The most important structures include:

The Temple:

Although its features are not clearly visible due to being beneath current village houses, it appears to have been a large building, as evidenced by its platform (podium), whose eastern section survives for about 40 meters. Large stone paving of the floor also remains.

An inscription on the exterior wall indicates that the Roman governor of Syria, Publius Helvius Pertinax (179–182 CE; later Roman emperor from December 193 to March 193 CE), “ordered the construction of the temple’s outer wall,” suggesting the temple’s construction predates this period.

In addition to the temple, there are numerous rock-cut structures, including many olive and grape presses, residential houses, tombs of various shapes and sizes, and stone quarries. About 2 km east of the town lies a site covered with basalt rocks, on which dozens of Safaitic inscriptions and drawings have been carved.

Roman-Era Tombs in Hinah:

Dozens of tombs dating back to the Roman period are spread throughout the town and its surroundings, featuring various types. Some are sarcophagi carved from limestone, others are rock-cut tombs and niches, and many are simple graves, the most common type, built from regular stones or finely dressed stone slabs.

The most notable cemeteries are located in the southern part of the town, still used by locals for burials. Their elaborate rock-cut design indicates they were likely reserved for the wealthy. These tombs vary in shape: individual or collective, with entrances on their roofs or walls. On the façade of one tomb, two half-statues and a Greek inscription commemorate a person named Archelaos.

In the eastern and northern parts of the town, many tombs built from roughly dressed and finely dressed stones also exist. The Rural Damascus Antiquities Department excavated several of these, notably three adjacent tombs on the eastern slope of Tell Hinah, which were similar in shape and contents. The tombs are spaced about 2.5 meters apart, built with finely dressed limestone walls, and covered with basalt slabs, measuring approximately 220 × 90 × 100 cm.

These tombs were used multiple times. One tomb contained the remains of three adult women, placed supine with heads to the north and feet to the south. Funerary furniture was placed at the head and feet of the deceased, including:

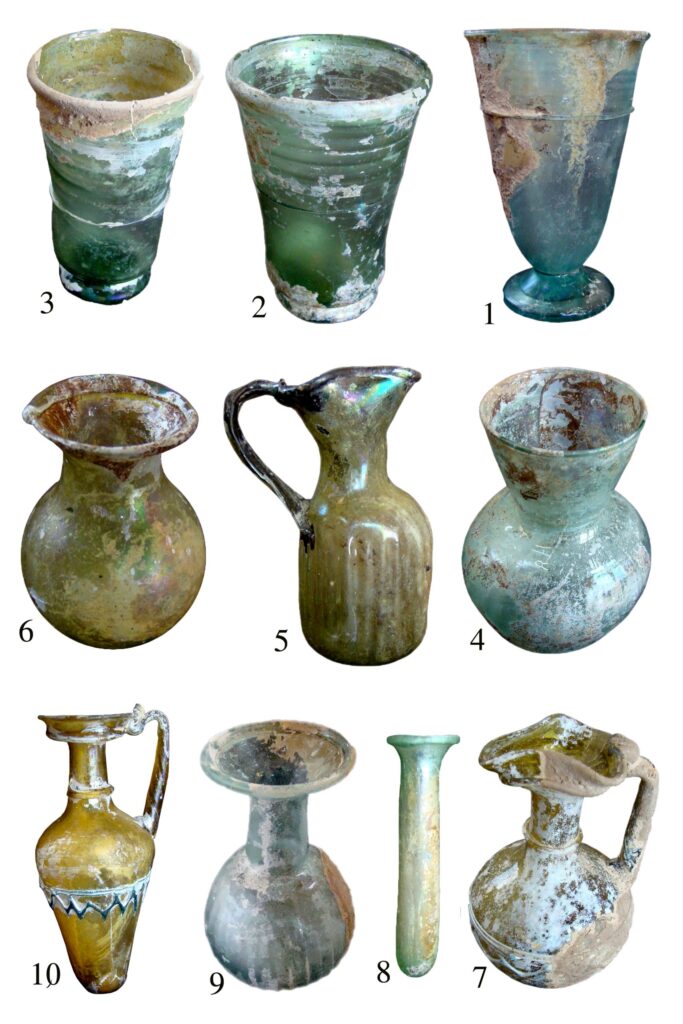

- Glass cups of various sizes, some decorated.

- Delicate glass bottles and flasks.

- Pottery vessels, including cups, a jug, bowls, an incense burner, and a fruit plate.

- A small decorated pottery vessel shaped like a starling bird.

- Jewelry such as gold earrings and rings.

- Collections of rings, necklaces, and beads made of glass, wood, or stone.

- Glass bracelets and full sets of armlets.

- Stone spindle whorls.

- Remains of shoes made from iron and leather, similar to those found in a tomb in Taybeh (south of Al-Kiswah) excavated in the early 1960s.

Tombs at the nearby Tell al-Kurum also contained some funerary items, such as glass cups and simple jewelry. Some tombs were empty of skeletal remains, containing only ashes, suggesting that cremation before burial was a known custom in the region since the Chalcolithic period and became widespread from the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, continuing into the Roman period.

Among the important finds in Hinah are numerous grave markers with Greek or Latin inscriptions, often with emotional content. Examples include:

Another marker measuring 92 × 33 cm from 186 CE, reading: (“Here I rest. My name is Agrippinos, son of Amarouros. I died very young at the age of 22. I was an orphan raised by my grandmother and uncles”).

A marker measuring 110 × 36 cm from the 3rd century CE with a five-line inscription: (“Be brave, Barichbelos, no one is immortal”).

Third: Hinah in the Byzantine Era

The town of Hinah contains many Byzantine archaeological landmarks, the most important of which are the remains of buildings and grape and olive presses, some of whose floors were paved with limestone (as in Tel al-Kurum). There are also several communal tombs, each associated with a specific family, the most important of which are three:

- The first: Found near the municipal building, it is a small rectangular chamber measuring 375 × 250 × 175 cm, constructed of basalt and carved limestone. It is accessed via a staircase leading to the entrance, followed by a vestibule in front of six graves positioned along the inner façade, distributed over two levels with three graves on each (only the ground-level graves remain due to damage).

The graves contained some scattered bones along with funerary objects dating back to the 5th and 6th centuries AD, including pottery vessels, decorated lamps, and some jewelry such as beads and metal and glass bracelets, as well as belt buckles, bells, some coins, and spindles for weaving.

- The second: Found on the eastern slope of Tel Hinah, it has the form of a typical grave. Built from limestone and basalt and covered with basalt slabs, it measures 185 cm deep, 210 cm long (west to east), with a width of 100 cm at the base narrowing to 75 cm at the top. It contained more than thirty skeletons or skeletal remains of women, children, and adult men, laid on their backs, sometimes stacked over one another, and sometimes placed side by side on the same level. In other levels, the bones of previously deceased individuals were collected in a corner of the grave to make room for a new burial, usually separated by a thin layer of soil.

The funerary objects in this tomb included some jewelry such as bracelets, beads, and rings, most made of bronze and glass, as well as ceramic lamps, bronze bells, and other artifacts dating back to the 5th and 6th centuries AD.

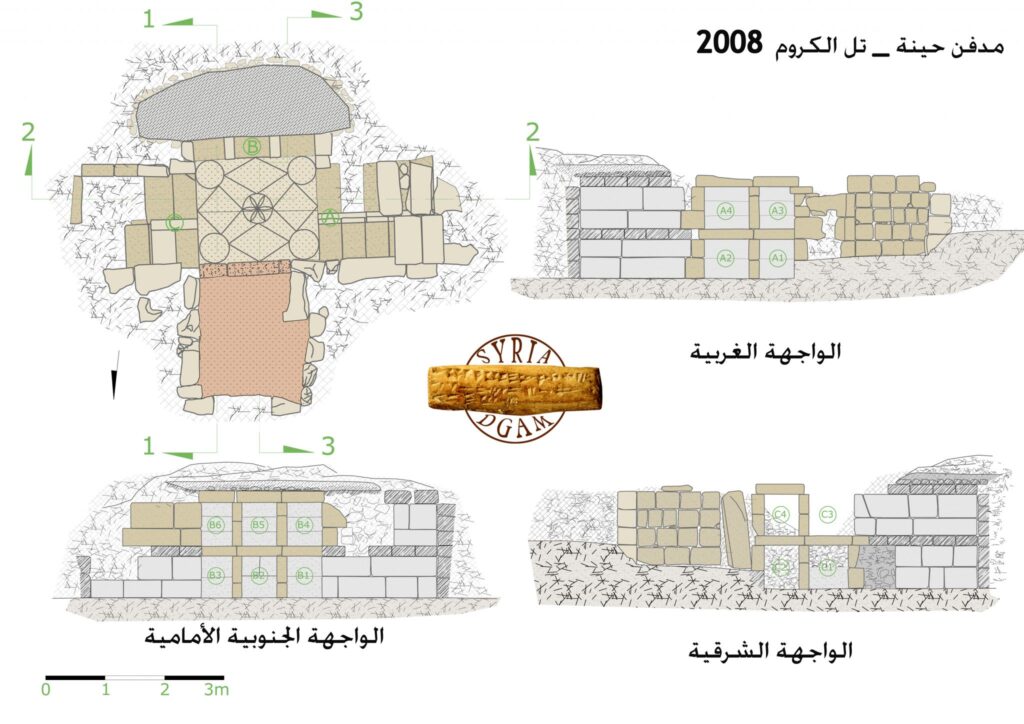

- The third: Found in Tel al-Kurum, discovered in 2008, and later subjected to vandalism and looting. It consists of a burial chamber preceded by a corridor built of limestone and basalt. The tomb measures 6 m in length and 6.75 m in width (west to east), with a height of about 2 m. It has a north-facing entrance, followed by a short corridor leading to another entrance, then the burial chamber with a vestibule measuring 200 × 175 cm. The chamber floor is made of a layer of lime decorated with geometric patterns. The tomb contains 15 graves distributed over two levels surrounding the chamber on three sides.

In the vestibule, a ceramic jug, a glass jug, and approximately fifty ceramic lamps were found, which were used by visitors during certain occasions. It is known that Christian clerics placed great importance on lamps because they symbolize the eternal light sought by the Church for the deceased and represent the glory enjoyed by saints in the presence of the Almighty, as light is considered an element of heavenly happiness. Therefore, lamps played an important role in funerary traditions and were considered part of the deceased’s furnishings, placed in the grave or in small windows or niches.

The construction of this tomb is unique in the Damascus region. It is similar to tombs in Zakiyah and Taybeh in southern Damascus, as well as sites in the Golan, Palestine, and Jordan. However, its construction technique resembles coastal tombs, especially in Amrit, even though these predate the Hinah tomb by several centuries.

Studies of the lamps indicate they belong to three groups: the earliest from the late Byzantine period (6th–7th centuries), a second group from the Umayyad era, and a third from the early Abbasid period. This suggests that this tomb, likely belonging to a Christian family, remained in use for over three hundred years under the rule of multiple political systems: Byzantine, Umayyad, and Abbasid.

Finally, the abundance and variety of buildings and archaeological landmarks in Hinah, especially the tombs and their funerary furnishings, indicate a state of social and political stability in the region throughout different historical periods, accompanied by diverse economic activity—commercial, industrial, agricultural, and pastoral—resulting in a high level of material wealth among the inhabitants, reaching its peak during the Roman and Byzantine eras, making the town a major and important center for the entire Hermon region.