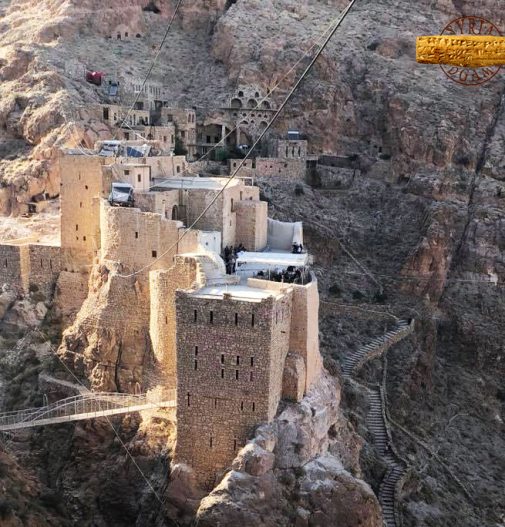

Mar Moussa al-Habashi Monastery is located 90 km north of Damascus and 16 km east of the city of An-Nabk, on the Al-Arqoub road. Nestled within a narrow mountain pass, it sits atop an isolated rocky outcrop on three sides, naturally forming an almost impregnable fortress. For this reason, the Romans turned it into a tower to monitor the ancient road used by caravans traveling between Damascus and Palmyra. In the 6th century AD, it became a monastery for monks and the residence of the monk Mar Moussa al-Habashi, an Abyssinian prince who left his father’s court and homeland in search of God’s kingdom. He migrated to Egypt, visited the holy sites in Palestine, and eventually settled in Mar Ya’qub Monastery near the town of Qara, north of An-Nabk, to lead a monastic life.

Seeking greater solitude and asceticism, he later moved to the monastery valley and lived in one of its caves as a hermit. During the religious conflicts among Christians of that era, following the Council of Chalcedon, the monk Mar Moussa was martyred by the emperor’s soldiers. News of his martyrdom reached Abyssinia, prompting a messenger from his family to retrieve his body and bury it in his birthplace. The locals were reluctant to part with the relics of their saint, and when they opened the grave, they found his right thumb detached from the body. This was seen as a divine sign, and the monks kept the thumb as a sacred relic, which remains preserved today in the Syriac Church of An-Nabk.

Some researchers suggest that the monastery was originally founded in the name of the Prophet Moses (Musa al-Kalim, peace be upon him). Monks and the local people preserved the story of Saint Moussa al-Habashi, who was martyred at the site in the monastery’s early history. His life became closely linked to the monastery’s foundation, as it is customary for monks to honor the founder of their monastery as a saint and intercessor.

The monastery’s early lifestyle followed the “laura” system—a form of hermitic monastic life. Monks lived in small individual cells within the mountain, connected by narrow paths leading to the church, guesthouse, and other communal facilities, similar to the semi-hermitic life in the lauras of the valleys east of Jerusalem. Many of the cells were later abandoned, and the monastery was rebuilt on a larger scale around a bigger church as monastic life shifted from solitary asceticism to communal living.

The monastery became a spiritual and cultural center in the region overlooking the desert, serving as a point of contact between the Arabic-speaking Bedouins and the Syriac-speaking urban populations. It was also a stop for pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem from Mesopotamia and northern Syria.

The monastery flourished and, by the 6th century, became an independent episcopal seat. The current church, according to Arabic inscriptions on its walls, dates back to 450 AH / 1058 AD. From the 15th century onward, the monastery was expanded, adding several structures including a small church with three wings, decorated inside with frescoes.

Monastic life continued until 1831 when the last monks left, leaving the monastery abandoned. Shepherds used it as a shelter for themselves and their livestock. Despite the lack of permanent residents, the people of An-Nabk continued to visit for blessings, and the local parish took responsibility for its upkeep.

The main buildings include the central church, and around the monastery in the rugged mountainous area, there are caves used as hermitages by monks since the Middle Ages.

The church itself dates to the mid-11th century, as indicated by inscriptions on the eastern and western walls. Cross engravings on the columns and walls are from the same period. The church consists of two main sections: the nave and the sanctuary. The square nave, approximately 10 meters per side, contains three aisles separated by columns, with a relatively large window illuminating the central aisle from the east wall. The sanctuary, housing the altar and apse, is separated from the nave by a barrier built of stone at the bottom and wood at the top, with a stone altar inside the apse decorated with simple geometric patterns.

The church walls are adorned with frescoes depicting scenes from the Bible and inscriptions in Arabic, Syriac, and Greek. These consist of three layers:

- The first layer, the oldest, dates to 450–488 AH / 1058–1095 AD, according to an inscription on the eastern wall of the northern aisle. These rare frescoes reflect the continuity of Hellenistic (Greek) Christian-Syriac art, evident in their sense of movement, vitality, and expressive power. Most of this layer remains beneath subsequent layers.

- The second layer dates to the late 11th century and shows refined spiritual and artistic sensibilities, reflecting the development of Byzantine art in the region.

- The third layer contains Arabic inscriptions written in lime, dated to 1192 or 1208 AD. These frescoes, distributed across all church walls, have a Syriac character, evident in the use of Syriac writing, the simplicity and spontaneity typical of Syriac art, and their thematic distribution, which contrasts with the more rigid and formalized Byzantine styles of the period.

The monastery was registered as a national heritage site under Ministerial Decree No. 63/A on 4/11/1957. Restoration and rehabilitation began in 1984 with contributions from the Syrian government (represented by the Directorate of Antiquities of Rural Damascus), the Italian government, the local church, and volunteers from the Arab and European world, including the Italian monk Paolo Dallolio. He published a book in 1998 documenting the monastery’s history, archaeology, and restoration works. Monastic life was revived under the care of the Syriac Catholic Archeparchy of Homs, Hama, and An-Nabk.

The construction of the church dates back to the mid-11th century AD, as evidenced clearly by inscriptions engraved on the eastern and western walls. The carved crosses on the columns and walls also date back to the same period. The church consists of two main sections: the nave and the sanctuary (Holy of Holies). The nave is square-shaped, with each side measuring approximately 10 meters, and is divided into three aisles running from west to east, separated by columns. A relatively large window in the eastern wall illuminates the central aisle.

The sanctuary contains the altar and the apse, separated from the nave by a partition whose lower part is built of stone and the upper part of wood. A stone altar, adorned with simple geometric decorations, is positioned within the apse.

The walls of the church are adorned with frescoes depicting precise representations of certain Biblical stories, alongside a collection of ancient inscriptions in Arabic, Syriac, and Greek. These artworks are organized into three layers:

- The first layer (the oldest) dates back to the period between 450–488 AH / 1058–1095 AD, according to the inscription on the eastern wall of the northern aisle. These rare frescoes reflect the continuity of Hellenistic (Greek) Syrian Christian art, evident in their sense of movement, vitality, and expressive power. Most of these paintings remain beneath the later layers.

- The second layer belongs to the late 11th century and is characterized by the painter’s refined spiritual and artistic sensibility, illustrating the development of Byzantine art in the region.

- The third layer carries Arabic inscriptions written in lime and is dated to 1192 or 1208 AD. Its significance lies in its widespread distribution across all church walls and its Syriac character, apparent from the use of Syriac script, simplicity, and spontaneity—traits typical of Syriac art. The thematic distribution of this layer contrasts with Byzantine patterns, which had begun to move toward more defined and fixed forms during that era.

The monastery was registered on the national list of archaeological sites by Ministerial Decree No. 63/A on November 4, 1957.

Restoration and site rehabilitation work began in 1984, with contributions from the Syrian government (represented by the Directorate of Antiquities of Rural Damascus), the Italian government, the local church, and a number of Arab and European volunteers, including the Italian monk Paolo Dallolio, who published a book in 1998 containing all the historical and archaeological information related to the monastery and the restoration work that had taken place and continues to this day. He also revived monastic life there under the supervision of the Syriac Catholic Archdiocese of Homs, Hama, and Al-Nabk.